Electronic money licensing is often approached as a regulatory milestone to be cleared before growth can begin. In reality, regulators do not view an electronic money license as an administrative or legal checkpoint. From a supervisory perspective, granting an electronic money license is an assessment of whether a firm is already capable of operating safely, transparently, and reliably within the financial services system.

For professionals already active in FinTech, this distinction is critical. Regulators do not grant an electronic money institution license based on business ideas, pitch decks, or compliance intentions. They grant it based on operating models and pre-configured compliance frameworks. What is evaluated in an electronic money license application is not whether a PayTech understands the rules, but whether those rules are embedded into its governance, operations, systems, and daily decision-making.

This article examines electronic money licensing through a regulator’s lens, translating supervisory expectations into operational realities. We explore how regulators assess readiness across governance, systems and controls, transaction processing, record keeping, AML/CTF, safeguarding, resilience and business continuity, and information security, as well as why many electronic money license applications fail despite substantial documentation.

- Electronic Money Licensing Is an Operational Test, Not a Legal One

- Governance and Accountability: The First Credibility Signal for an Electronic Money License

- Customer Onboarding as a Risk Control in Electronic Money Licensing

- Ledger Integrity as the Foundation of an Electronic Money License

- Transaction Processing as Proof of Control in an Electronic Money Institution

- AML/CTF as a Continuous Obligation Under an Electronic Money License

- Safeguarding and Reconciliation in Electronic Money Licensing

- Reporting, Resilience, and Security Under an Electronic Money License

- An Electronic Money License Is Ultimately About Operational Credibility

- Electronic Money Licensing Is a Design Choice

Electronic Money Licensing Is an Operational Test, Not a Legal One

Regulators approach an electronic money license application as a forward-looking risk assessment. The question is not whether a firm plans to comply, but whether compliance is already embedded by design.

Supervisory authorities seek evidence that risks are understood, controlled, and monitored continuously before granting an electronic money license. They examine whether policies translate into systems configuration, capabilities, and behaviour, whether responsibilities are clearly allocated, and whether the applicant can demonstrate control through audit trails rather than assurances.

This is why electronic money licensing delays frequently occur even when the documentation pack appears complete. Policies may exist, but operational reality reveals gaps: excessive reliance on manual processes, unclear accountability, fragmented systems, or weak data integrity. From a regulator’s perspective, such weaknesses signal potential future compliance failures and even supervisory intervention.

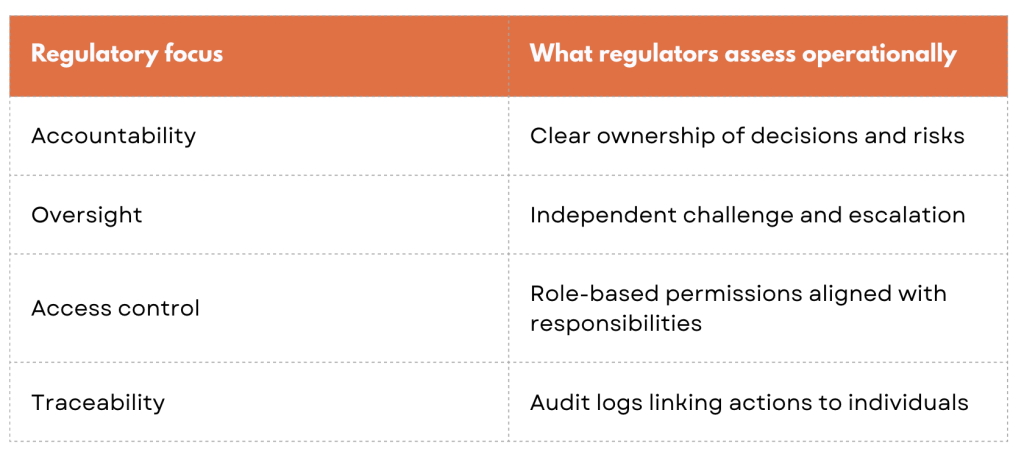

Governance and Accountability: The First Credibility Signal for an Electronic Money License

Governance is typically the first area regulators examine during an electronic money license application, because it shapes every other control. A firm’s governance framework reveals how decisions are made, which controls are implemented, how risks are escalated, and how accountability is enforced.

Regulators assess whether authority and oversight are clearly separated, even in early-stage firms applying for an electronic money institution license. Concentration of power where a single individual controls operations, compliance, and systems is viewed as a structural risk, regardless of company size. What matters is proportionality, not headcount. Moreover, regulators assess whether key personnel are fit and proper and possess the required experience — again, this is not about the number of people but about whether senior managers can confidently cover regulated areas within an electronic money framework.

Crucially, governance must be reflected in system access. Regulators increasingly treat access control as a substantial governance mechanism rather than a technical detail when assessing an electronic money license application. If an organisational chart shows separation of duties, but core operating system permissions allow unrestricted access, regulators will be guided by system capabilities over narrative.

From a regulatory perspective, weak governance rarely manifests as an explicit absence of structure. More often, it appears as informal decision-making, undocumented exceptions, or reliance on personal trust rather than enforceable controls. During an electronic money license review, regulators pay close attention to how governance operates under pressure — during incidents, rapid growth, or personnel changes — because these moments expose whether accountability is institutionalised or merely implicit.

As a result, supervisors increasingly expect applicants for an electronic money license to demonstrate that governance principles are operationalised through workflow approvals, access limitations, and escalation paths that function consistently over time.

Table 1: Governance Through a Regulator’s Lens

Customer Onboarding as a Risk Control in Electronic Money Licensing

From a regulatory perspective, customer onboarding in an electronic money institution is not a user experience challenge. It is a gatekeeping mechanism that determines who is permitted to access regulated financial services under an electronic money license. A clear real-world example of these divergent views comes from the experience of N26. In 2021, Germany’s financial regulator, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin), imposed a cap on the number of new customers N26 could onboard per month as part of enforcement actions tied to shortcomings in the bank’s anti-money-laundering (AML) compliance and customer due diligence controls.

Regulators assessing an electronic money license application evaluate whether onboarding processes reliably prevent anonymous, high-risk, sanctioned individuals, or bad actors with stolen or synthetic identities from accessing financial services.

Automated onboarding is acceptable within an electronic money framework, but only when supported by defined escalation paths and robust risk scoring. Regulators expect human intervention for complex or high-risk cases, with decisions documented and defensible. An applicant that cannot explain why a specific customer was approved or rejected is viewed as lacking operational control, regardless of automation sophistication.

Consistency remains central to electronic money licensing. Discretion without structure creates risk. Well-designed onboarding processes apply consistent standards and leave an auditable trail of decisions.

Ledger Integrity as the Foundation of an Electronic Money License

If governance establishes accountability, the ledger establishes auditability in an electronic money institution. From a regulatory perspective, the ledger is the primary evidentiary record of a firm’s financial reality when assessing an electronic money license application. Customer funds balances, movements, fees, and adjustments must be traceable to a coherent accounting structure that reflects events accurately over time.

Fragmented ledger architectures remain one of the most material weaknesses identified during an electronic money license review. When customer balances are calculated across multiple systems, derived dynamically rather than recorded deterministically, or subject to manual adjustments without clearly documented approval and audit controls, regulators question the reliability of all downstream financial reporting required under an electronic money license. In such environments, even minor discrepancies can trigger supervisory concern, as they indicate that the electronic money institution may struggle to explain its financial position with precision under audit scrutiny or stressed conditions. This risk has been demonstrated in practice.

This concern has been evidenced in practice, for example, in the case of Revolut, where auditors repeatedly highlighted difficulties in obtaining sufficient assurance over reported balances due to complex, fragmented ledger architectures and reliance on reconciliations across multiple internal systems, delaying the completion of audited accounts and reinforcing supervisory concerns about balance accuracy and explainability, as reported by the Financial Times.

Ledger integrity underpins safeguarding, reconciliation, reporting, and audits. Regulators’ confidence in granting or maintaining an electronic money license often rises or falls with their confidence in the applicant’s ledger architecture. Safeguarding relies on accurate, point-in-time representations of customer funds. Reconciliation processes depend on ledger entries that can be matched cleanly against external accounts. Regulatory and management reporting assumes that ledger data is complete, immutable, and internally consistent. Audits, both internal and external, are only as credible as the ledger they are based on. For regulators, weaknesses in ledger design often signal broader control deficiencies, regardless of how robust other processes may appear.

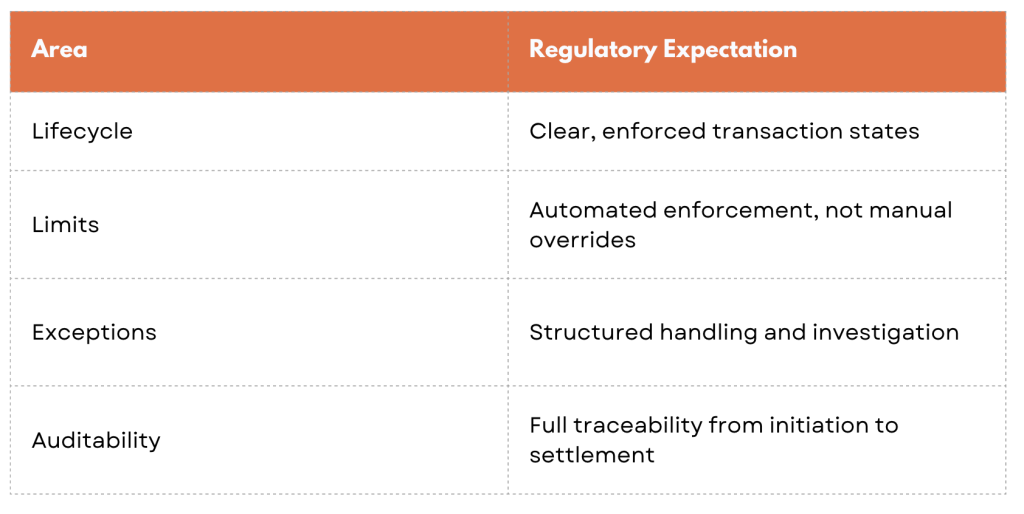

Transaction Processing as Proof of Control in an Electronic Money Institution

Transactions are where electronic money licensing expectations are tested in real time. Regulators do not merely review transaction rules; they assess how transactions behave throughout their lifecycle.

Each transaction must follow predictable states, enforce limits, and leave a clear audit trail within the electronic money institution’s core system. Failures, reversals, and corrections must be controlled rather than improvised. Unexplained anomalies signal weak internal controls, which is something regulators will not tolerate in an electronic money license holder.

Regulators observe not only whether transactions complete successfully, but also whether the system consistently prevents unauthorised actions, detects abnormal behaviour, and responds deterministically to errors. A transaction that can bypass validation logic, exceed defined limits, or be manually altered without a trace is treated as a systemic control failure rather than an isolated incident.

Over time, patterns of small inconsistencies or ad-hoc interventions raise greater concern than singular technical issues, as they indicate that controls exist in theory but are not enforced in practice. For this reason, regulators expect transaction processing engines to operate as control mechanisms in their own right, embedding regulatory requirements directly into the execution logic rather than relying on downstream monitoring or human correction.

Table 2: What Regulators Look for in Transaction Processing

Transactions provide regulators with tangible evidence of whether controls work in practice, not just in theory.

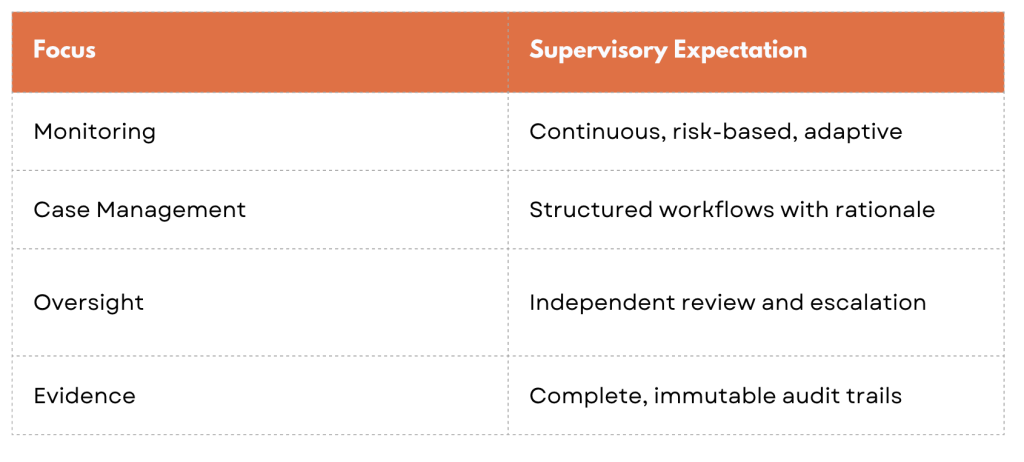

AML/CTF as a Continuous Obligation Under an Electronic Money License

Anti-money laundering obligations under an electronic money license are continuous, not event-driven. Regulators do not view AML/CTF as a set of onboarding checks or reporting obligations. They view it as a continuous assessment of customer behaviour and transactional risk. The UK Financial Conduct Authority’s enforcement action against Monzo illustrates regulators’ expectation that AML/CTF operates as a continuous, behavioural control.

The FCA found that while Monzo had onboarding checks and monitoring tools in place, its systems and processes did not adequately adapt to changes in customer behaviour and transaction risk as the business scaled, leading to weaknesses in alert handling, escalation, and ongoing risk assessment. The regulator explicitly framed the failure as one of ongoing risk assessment and operational governance, rather than a lack of tooling, reinforcing the expectation that AML/CTF must function as a continuous, well-governed operational process.

Supervisory authorities evaluate whether electronic money institutions can detect behavioural changes over time, not just static risk at onboarding. Monitoring rules must adapt to customer profiles, and alerts must be reviewed through structured case management.

What matters most in an electronic money license review is not the presence of AML/CTF tooling, but the explainability of decisions. When an alert is closed, when monitoring thresholds are changed, or when a report is filed or not filed, regulators expect to see clear reasoning supported by evidence.

AML failures often arise not from intent but from operational overload: lack of an internal notification system, too many alerts, unclear ownership, or weak escalation processes. Regulators, therefore, scrutinise whether AML operations are sustainable and governed within the electronic money framework.

Table 3: AML/CTF Through a Regulatory Lens

Safeguarding and Reconciliation in Electronic Money Licensing

Safeguarding customer funds is central to every electronic money license.

Regulators approach safeguarding as a daily operational control, not a contractual arrangement. The UK Financial Conduct Authority’s decision to overhaul the safeguarding regime for e-money and payment institutions provides a clear real-world example of regulators treating safeguarding as an operational discipline rather than a legal construct. Following multiple failures of payment and e-money firms where customer funds were exposed despite formal safeguarding arrangements, the FCA concluded that weaknesses consistently arose from poor daily reconciliations, unclear ownership of safeguarding processes, and system limitations that prevented firms from detecting discrepancies in a timely manner.

As a result, the FCA transposed key principles of the client assets regime (CASS) into the payments sector with the introduction of PS25/12 policy statement, explicitly requiring firms to demonstrate continuous segregation, frequent reconciliation, documented reviews, and auditable evidence of how discrepancies are identified and resolved in practice.

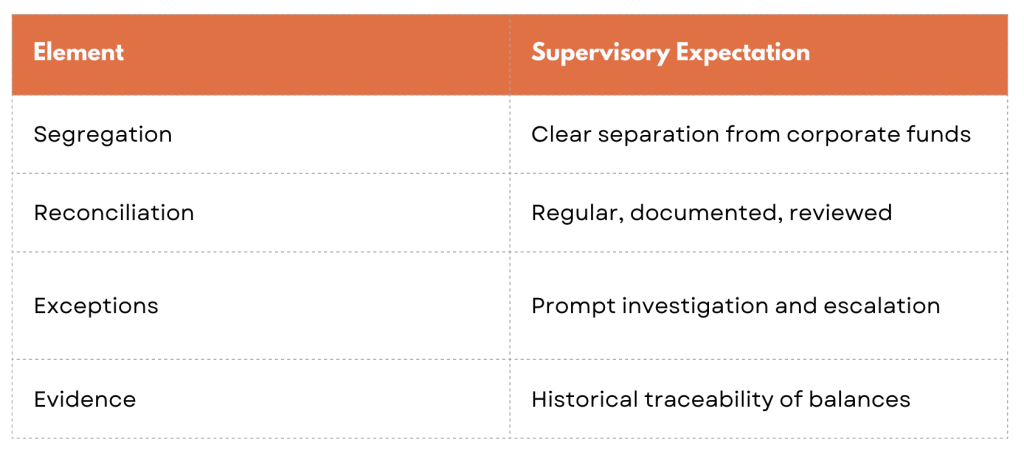

Weak reconciliation processes are among the most common causes of supervisory concern in electronic money license holders. Regulators expect clear ownership, documented reviews, and historical traceability of balances.

Strong safeguarding frameworks significantly strengthen an electronic money license application and reduce supervisory intensity post-authorisation.

Table 4: Safeguarding Expectations

Reporting, Resilience, and Security Under an Electronic Money License

Beyond daily controls, regulators assess whether an electronic money institution can withstand disruption and remain transparent under stress.

This includes producing accurate regulatory reports, maintaining immutable audit trails, managing third-party risk, and protecting sensitive payment data. Increasingly, regulators also focus on third-party risk, treating vendor access as an extension of the electronic money firm’s own control environment.

Operational resilience is no longer limited to technology uptime. It encompasses people, processes, systems, and dependencies. Regulators expect firms to identify critical functions, test recovery scenarios, and demonstrate incident learning.

An Electronic Money License Is Ultimately About Operational Credibility

Viewed through a regulator’s lens, an electronic money license is a validation of credibility rather than ambition. Regulators are not persuaded by growth plans or market narratives. They are persuaded by evidence of risk control embedded in governance, systems, and operations.

Firms that succeed in securing an electronic money institution license share common traits: clear governance, enforced controls, comprehensive and reliable core operating systems, and auditable processes. Those who struggle often attempt to retrofit operational discipline after launch, when complexity and risk have already increased.

Early architectural and operational decisions profoundly influence electronic money licensing outcomes. What regulators ultimately evaluate is not effort, intent, or sophistication of policy documentation, but operational credibility. They look for evidence that governance is real rather than nominal, that controls are enforced by systems rather than people, and that risks are identified, monitored, and managed continuously rather than episodically. A firm that can explain how decisions are made, how exceptions are handled, and how historical events can be reconstructed signals maturity far more convincingly than one that simply references policies.

Electronic Money Licensing Is a Design Choice

Viewed through a regulator’s lens, an electronic money license is not a procedural checkpoint. It is an assessment of whether a firm is structurally capable of operating within the financial system without introducing unacceptable risk to customers, counterparties, or the market itself.

Licensing outcomes are often determined long before an electronic money license application is formally submitted. Architectural choices, operating models, and control design decisions made early in a firm’s lifecycle either support regulatory confidence or undermine it. Attempting to retrofit governance, auditability, or safeguarding into a live environment is not only costly but also frequently exposes weaknesses that regulators cannot ignore.

For teams preparing for an electronic money license, the implication is clear. Licensing should not be treated as a legal project owned by external advisors and completed in isolation. It should be approached as a cross-functional exercise involving product, operations, engineering, risk, and compliance, with systems playing a central role in enforcing regulatory expectations. When controls depend on discipline alone, they eventually fail under scale.

This is where infrastructure decisions become strategic. Core banking architecture, access control models, transaction processing logic, and data governance frameworks are not implementation details from a regulatory standpoint. They are evidence of whether a PayTech understands the responsibilities that come with handling customer funds and data.

At Baseella, we support firms pursuing an electronic money license by embedding governance, auditability, safeguarding, and resilience directly into core banking infrastructure, aligning operational design with supervisory expectations and helping teams move beyond reactive compliance and toward sustainable regulatory readiness.

An electronic money license is not about convincing regulators you will comply in the future. It is about demonstrating that you are “fully organised, ready, and willing” to start the operations as if you already had a license secured. Those who internalise this distinction early not only navigate licensing more smoothly, but also build organisations capable of scaling with confidence in an increasingly demanding regulatory environment.

If you are preparing for an electronic money license application or reassessing your operational foundations, we invite you to speak with us. Understanding electronic money licensing through a regulator’s lens is not merely a compliance exercise; it is a competitive advantage.